The Evolution of AI Agents: From Static to Dynamic Training

AI Agents are on the Verge of Becoming Massively Better

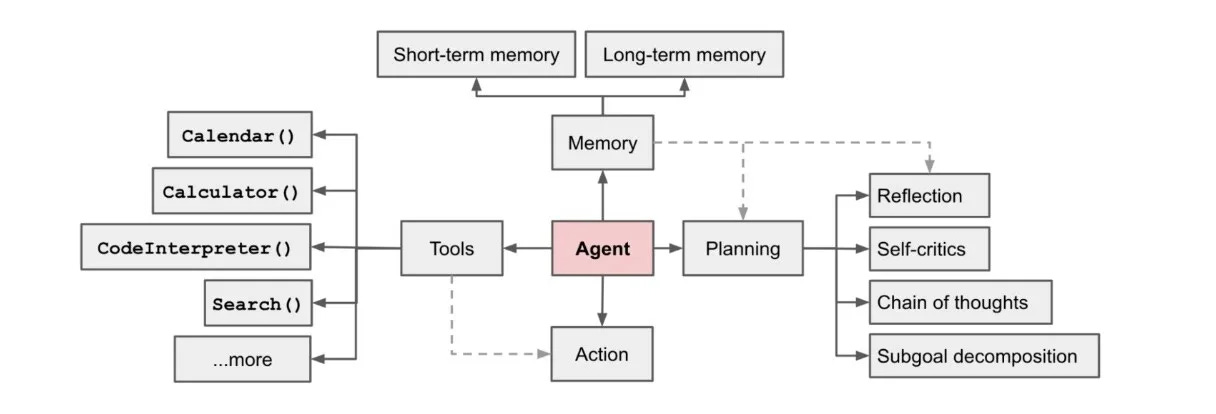

Last year, we saw a surge of startups jumping on the "AI agent" bandwagon, focusing on industry-specific applications. These agents sit at the frontier of AI automation, and typically involve:

A foundational model (LLM)

Memory capabilities

Planning abilities

Tools for environment interaction

The promise of these systems lies in their ability to use LLMs as reasoning engines, orchestrating memory, tools, and environment feedback to perform complex tasks—much like humans do.

Thanks for reading Anno’s Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribe

Notable examples:

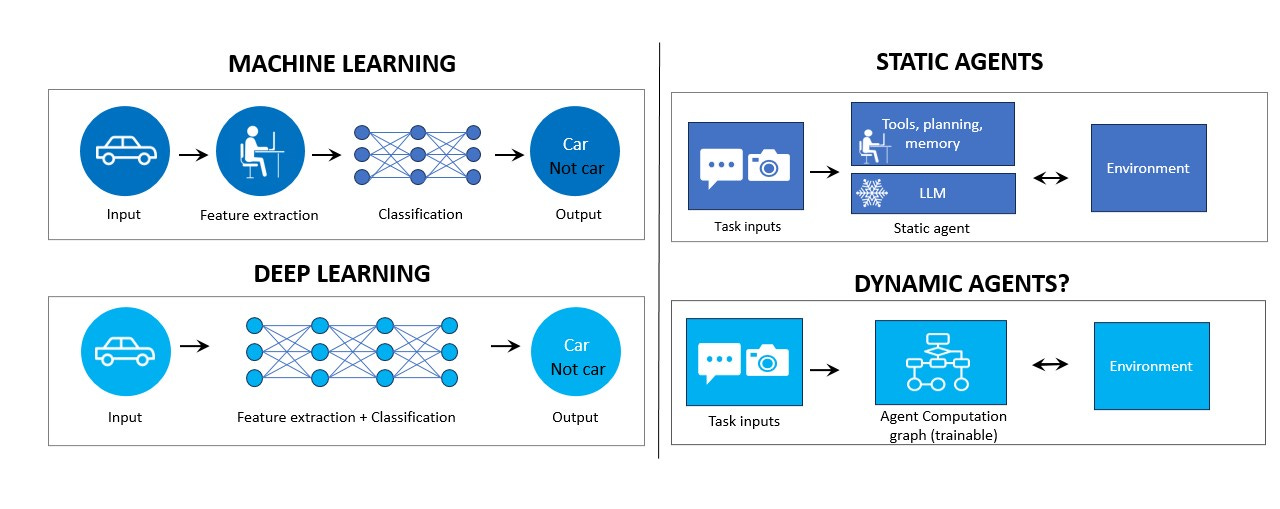

Current Approach: Static architecture and Its Limitations

Most deployed AI agents today operate on off-the-shelf LLMs with frozen weights. Adaptation to the environment typically involves:

Engineering better prompts

Better agent memory storage and fetching heuristics

Providing more fine-grained tools for environment interaction

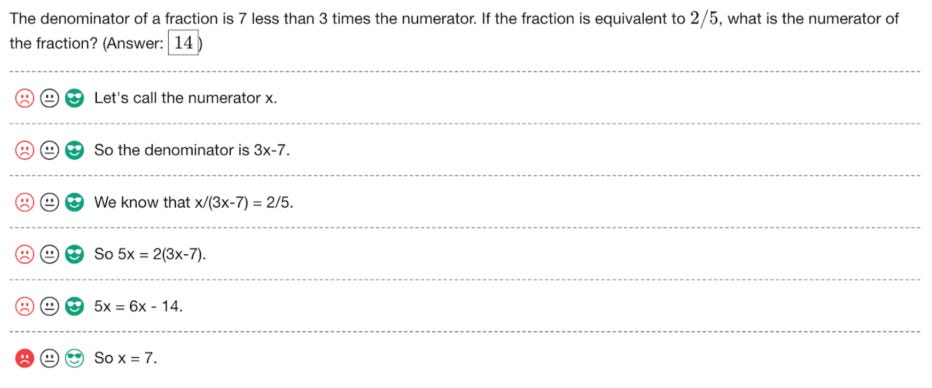

This approach was effective for initial product launches, but now we are hitting a plateau in agent performance. Why? As tasks grow in complexity, the potential states of the environment and the action spaces expand exponentially. This increased complexity introduces more edge cases, typically clutters agents context and planning, and raises the likelihood of errors that cumulatively lead to failures. A recent paper, have evaluated these failures, particularly in web environments.

The current engineering focus to boost performance is reminiscent of classical ML “feature engineering”, where human effort was dedicated to crafting better features for models to process.

The Code-Writing Agents Example

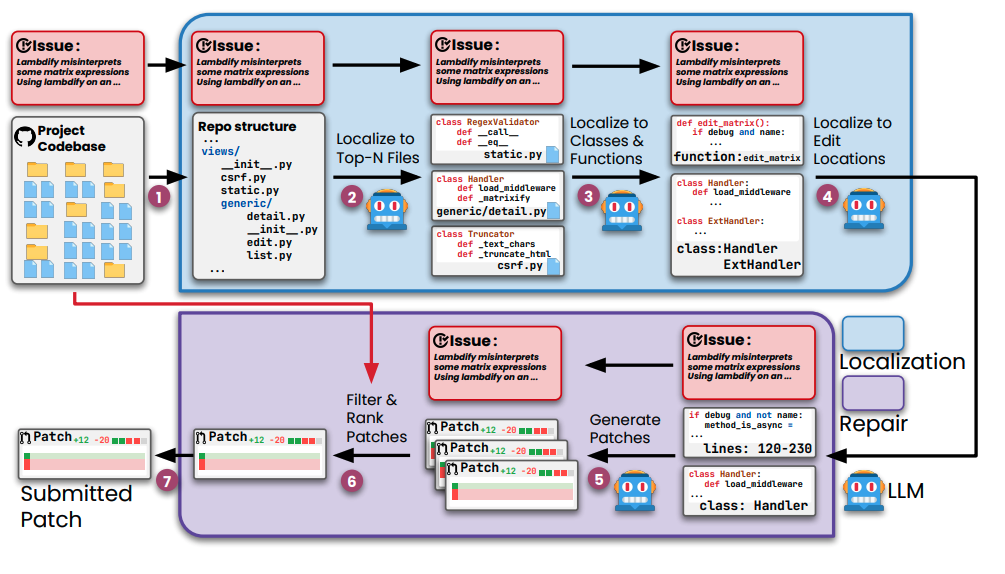

Code-writing agents illustrate this performance plateau. In the code domain, it's straightforward to evaluate an agent's performance on a task by simply running the corresponding tests. This clarity in evaluation highlights the limitations of the current static approach, as agents often struggle with the increasing complexity of coding tasks.

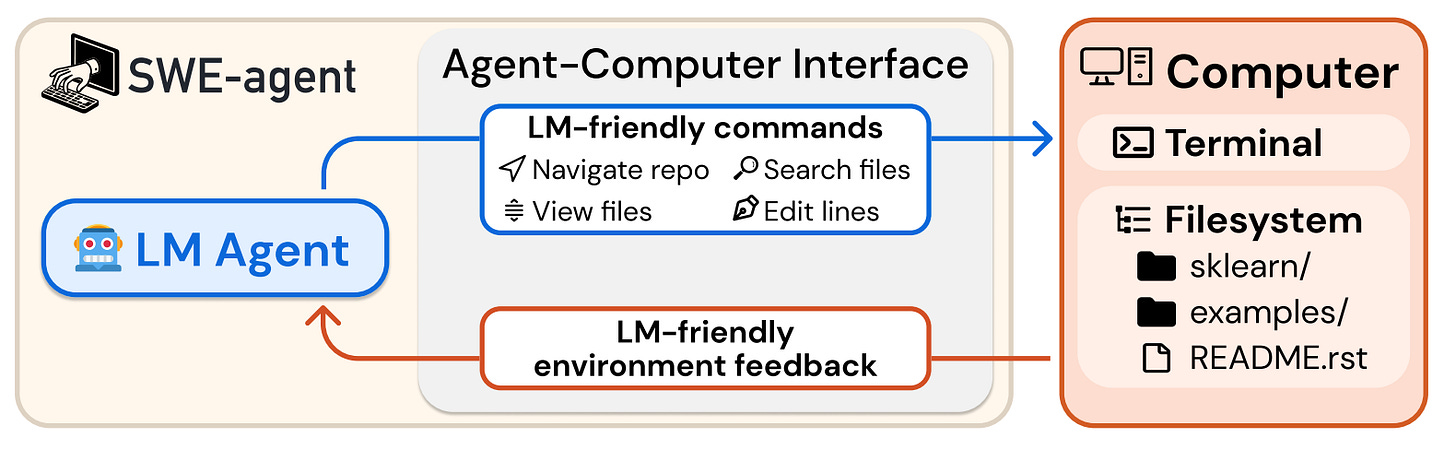

SWE-agent is a leading code-writing AI agent designed to autonomously fix bugs and address issues in real GitHub repositories. It interacts with a Docker container leveraging a cloned project and its dependencies. Interaction with the environment is done using engineered APIs (Tools) known as the Agent-Computer Interface. These APIs were shown to significantly enhance the agent's ability to navigate repositories, edit code, and execute tests.

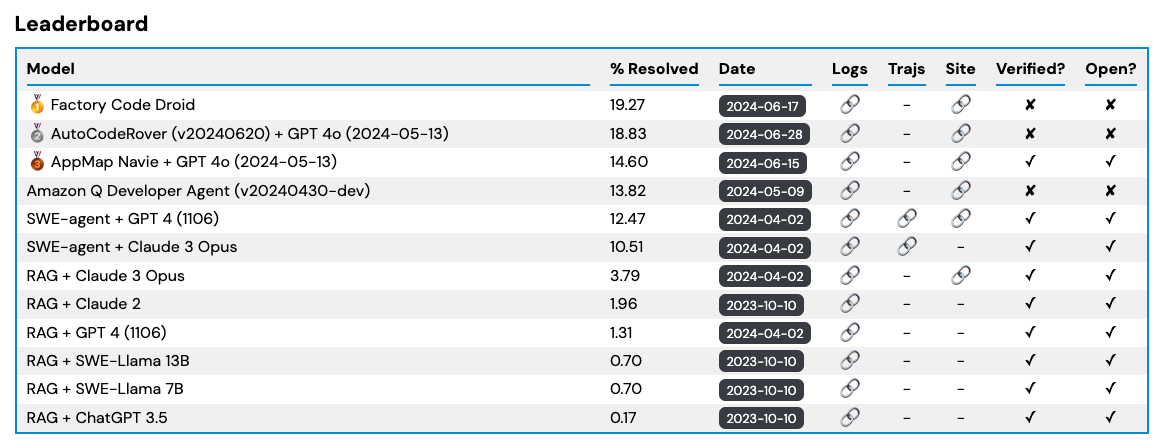

The SWE-bench benchmark evaluates coding agents using real GitHub pull requests that include corresponding tests from popular projects (numpy, flask, etc.). The leaderboard shows the current state: the best open-source agent (SWE-agent) has a 14.6% success rate, despite significant engineering efforts to simplify command structures, enhance environment feedback, and implement guardrails. Impressive results, but still a lot of room for improvement.

The same pattern emerges with web browsing AI agents. The recent WebArena benchmark revealed that these agents achieve only a 14% end-to-end task success rate (compared to 78% for humans).

Pushing Past the performance Plateau: Three Directions

1. Inductive Bias

The most common approach adopted by startups involves integrating assumptions and domain-specific knowledge to guide LLMs. This includes:

Authoring more agent-friendly tools

Crafting better prompts

Improving prompt chaining for more reliable results (e.g. prompt flow engineering)

This is necessary and goes a long way, for example the recent Agentless paper performed on par with top AI agents on SWE-bench-lite (a reduced, easier version of SWE-bench) by constructing a pipeline of prompts relevant for the task of fixing bugs. This also drastically reduced inference costs, which are notoriously high in agents.

2. Scaling Up

Another direction involves:

Larger, multimodal LLMs

Scaling feedback through learning from AI feedback

These lead to enhanced understanding across all tasks. This effort is mostly limited to the big players in the market due to compute costs, but we're already seeing signs of diminishing returns in vanilla LLM scale. Novel research in self supervision may surprise us. I'm fond of Meta’s JEPA line of papers.

A more accessible approach for startups is scaling down—fine-tuning small language models on specific tasks. This significantly reduces inference costs, sometimes even improves performance, and allows for running on low-resource endpoint environments. However, this isn't a major approach for a step-change in performance; it's more about cost and efficiency.

3. Back to Gradient Descent

The third, less-mainstream option takes us back to pre-ChatGPT days:

Applying gradient descent to the entire AI agent architecture

Optimizing multiple components simultaneously: memory, tool calls, prompts, and the LLM itself

Overcoming challenges with non-differentiable components in the optimization graph (differentiable approximations & straight through estimator)

This approach is still mainly in research and evolving. Two notable papers in this direction are Retroformer and Agent Symbolic Learning. Retroformer uses policy gradient optimization to tune language agent prompts based on environmental feedback. Agent Symbolic Learning treats agents as symbolic networks and mimics backpropagation using natural language. Both methods enable AI agents to evolve and improve autonomously after deployment, representing a shift from static to dynamic training. Another notable paper, RAFT, trains LLMs to ignore irrelevant documents when answering questions. OpenAI has also shown that human annotation for process supervision significantly improves LLMs in solving math problems.

The future may see a convergence of these approaches towards end-to-end optimization from feedback and experience rather than improving prompts and tools (feature engineering). Engineering efforts would shift to providing agents with supervision (augmented by AI) that directly optimizes the agent’s components.

In this envisioned future, agents will be built within a framework that facilitates end-to-end optimization of all components (memory, tools, prompts). For example, a coding agent could receive feedback on whether it utilized the correct debugging tool or accessed the appropriate code files. Similarly, a web browsing agent could learn from human demonstrations of tasks performed on websites. This setup would enable a unified compute graph, where gradients flow through every part—memory, tools, prompts—allowing for joint optimization and continuous improvement.

In essence, every agent component will function as a PyTorch module, where gradients are saved and propagated automatically, abstracting the graph constrution complexity and enabling seamless optimization across all components. Just like how PyTorch handles neural networks.

This approach raises several questions:

What new frameworks will emerge to support end-to-end agent training?

What will be the sample efficiency of such systems? How many experiences are needed to adapt to a new environment? Both are critical for mass adoption.

What are your thoughts on this shift? How do you see it evolving and shaping the AI landscape? How close do you think we are to achieving this level of flexibility in AI agents?

Thanks to Aner Mazur, Eddo Cohen, Liel Ran and Amit Mendelbaum for reviewing <3